Reports of ‘Id-ul-Adha

at Woking,

4th August 1922

Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din leads prayer and gives khutba

From The Islamic Review, October 1922

|

We present here reports relating to‘Id-ul-Adha at the

Woking Mosque on Friday 4th August 1922, taken from The Islamic

Review, October 1922. This is presented as an example of the

celebration of such festivals at the Woking Mosque in the early

years of the Woking Mission, to illustrate how these occasions were

conducted and the kind of international Muslim dignitaries who graced

them by their presence.

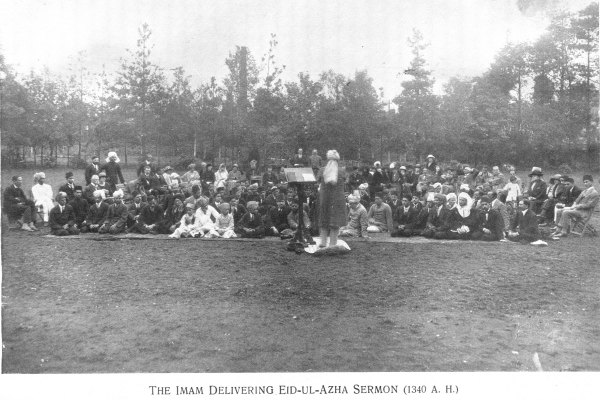

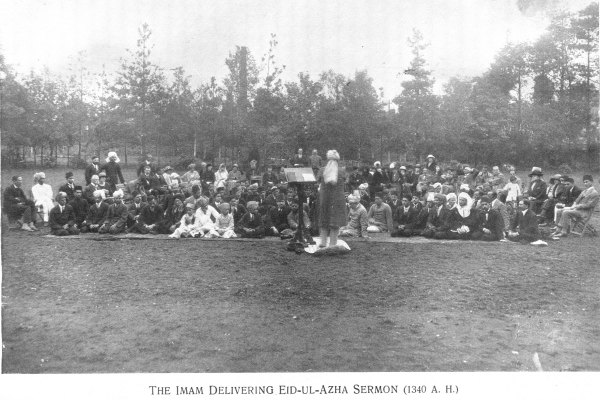

The photograph below shows the khutba being delivered in

the grounds of the Woking Mosque (see this photograph in a larger

size).

British Press coverage

In The Islamic Review, October 1922, on pages 409–413,

British Press comments on this‘Id-ul-Adha celebration

at the Woking Mosque are reprinted. We quote from these below.

The Times, August 5th:

About two hundred Mussulmans commemorated the festival

of Eid-el-Azha Qurban Bairam at Woking yesterday. The

feast celebrates the sacrifice of Abraham, venerated alike

by Jews, Christians and Mussulmans. After the picturesque

scene of the initial prayer on the lawn before the Mosque

an impressive declaration of faith was made by Princess

Hassan, an American by birth and an Egyptian by marriage.

Those present included the Imam (his Holiness the Khwaja

Kamal-ud-Din), who addressed the gathering, Lord Headley

(chief of the English Mussulmans), the Turkish Charge

d’Affaires, the Persian Ambassador, the Persian Consul

in London, His Highness the Amir-ul-Saltanat (of the Persian

Royal Family), Sahibzada Aftab Ahmed Khan (member of the

Council of the Secretary of State for India), and his

brother Sahibzada Sultan Ahmed (Minister of Gwalior).

The day’s proceedings laid emphasis on the Biblical

fact that the sacrifice made by Abraham called forth the

Divine injunction forbidding human sacrifice.

|

Westminster Gazette, August 5th:

On a Surrey lawn, under the open sky, I had the unusual

experience today of hearing an American woman solemnly declare

her adherence to Islam.

She wore furs and carried an immense aigrette in her toque,

had pearls about her neck, and held a vanity bag in her

gloved hands. Beside her stood a big, imposing, bearded

man in a dull white turban and a long, figured, buttonless

coat of a colour too faded and indeterminate to be easily

named. The woman repeated after him, firmly:

“I bear witness that there is no God or object of

adoration but one God, Allah. I bear witness that Mahomet

is the servant and messenger from Allah. I promise to

be a good Muslim.”

The convert was Princess Hassan. Her husband was first

cousin of the ex-Khedive Abbas Hilmi, and nephew of King

Fuad, but she herself was born in California.

The card which admitted me to this ceremony was printed

in gold type. Armed with this, I mingled with fezzes and

turbans, and watched Muslims prostrate themselves on the

lawn, their faces towards Mecca.

More nearly in front of them was a queer little building,

garish in red brick, and yet more garish in certain Moorish

embellishments which made the four chimney-pots look like

minarets. To their right was a small white, domed structure,

the only mosque in this country. Behind them, their noise

frequently bringing the preacher to a pause, rattled the

South Western expresses.

Three large carpets and some white tablecloths had been

spread on the wet grass, and at the side of them was a line

of boots and shoes which the worshippers had discarded.

On these carpets were Muslims from all over the world. The

black-bearded, handsome Afghan Minister and his suite were

there in woolly fezzes.

The Turkish Charge d’Affaires, a smaller and more

elderly figure in a red fez, arrived after the recital of

prayers. The Persian Ambassador was there, and the two slim

men in flowing black robes and white flannel hoods were

members of the Riff delegation. Lord Headley was the plain

English gentleman. Indian students were there, an Egyptian

from Birmingham, men of various dark-skinned races in a

variety of bright turbans, boys in gay raiment, and a few

smiling negroes.

They came to the carpets at the bidding of a picturesque

old man in an orange turban, who, with hands to his ears,

had raised the monotonously plaintive call to prayer —

the salat. An equally picturesque figure, on a clean straw

mat, led the prayers, read from the Quran and preached the

sermon. He was the Imam — the Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din of

the gold-lettered invitation card.

There was a spice of politics in his sermon, blended with

an exposition of the four attributes of Allah. “Allah

is Rabb-ul-alameen,” he said, “the creator, maintainer,

nourisher and evolver of all nations. Let those who are

the rulers of the world follow him in this first attribute,

and so secure the peace of the world without the mockery

of Genoa and the hopelessness of the Hague Conference.”

Another observation was: “Today you call a nation

bandits or cut-throats, and tomorrow you go and shake hands

with them as gentlemen, simply to serve your political ends

and to bring another nation to dust. That is not the way

to restore peace on the earth of the Lord on High.”

To “walk humbly with the Lord” was the Imam’s

prescription for the millennium.

When the service ended the worshippers rose to their feet

and embraced one another fervently. |

Woking News and Mail, August 11th:

Muslims from all countries in the world who are resident

in England assembled at the Mosque, Woking, on Friday, to

celebrate the Feast of Eid-ul-Azha Qurban Bairam, in commemoration

of the sacrifice of Abraham, the great patriarch of the three

religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the festival

coinciding with the annual pilgrimage to the Holy City of

Mecca. The festival at Woking was attended by upwards of two

hundred Muslims, many distinguished visitors being among them.

A number were wearing native garb with turban and fez, the

scene on the carpeted lawn at the call to prayer being a very

picturesque one. Among the company were Lord Headley (President

of the British Muslim Society), the Princes Aziz and Sadiq

of Mangrol, Her Highness Princess Hassan, H.E. Sardar Abdul

Hadi Khan (Afghan Minister) and suite, the Afghan Minister

at Paris, H.E. Reshid Pasha (Turkish Charge d’Affaires),

two members of the Riff delegation of the new Morocco Republic,

one being a brother of Emir Abdul Karim, the Republican President,

H.H. Amir-ul-Saltanat, a member of the Persian Royal Family,

Sahibzada Aftab Ahmad (member of the Council of the Secretary

of State for India), and his brother, Sahibzada Sultan Ahmad

(Minister of Gwalior), Dr. Abdul Majid (Muslim Jurist in London),

the Persian Ambassador and the Persian Consul in London.

There were representatives in attendance from Turkistan,

Afghanistan, Russia, India, Malay Peninsula, Arabia, Syria,

Palestine, Turkey, Switzerland, Egypt, Morocco, Tunis, America,

France, and from South, East, West and North Africa, as well

as many British converts to the Muslim faith, but the rainy

weather undoubtedly kept away many who would have been present

otherwise.

Following the call to prayer, which was conducted in the

open air by the Imam of the Mosque, Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, there

was an interesting ceremony, in which Her Highness Princess

Hassan declared her faith in Islam, and was admitted to the

community. The Princess is an American lady by birth, but

Egyptian by her marriage to a nephew of the former Khedive

of Egypt.

The Imam, who is the author of the recent book, India

in the Balance, and a leading authority in the Muslim

world, being responsible for the inauguration of the Muslim

mission in England, then delivered an eloquent address to

the assembled Muslims of all races and colour.

In the course of his address the Imam said they met that

day to revere Abraham in commemoration of the great sacrifice

he found himself prepared to make at Mina, a place only seven

miles distant from Mecca, where representatives from the whole

Muslim world were assembling that day in connection with their

pilgrimage to that Holy City. His was a great sacrifice —

a sacrifice which must inspire every believer today to be

ready to offer up to God what was most near and dear to them,

be it wealth, or love, or life, in the cause of God, which,

from the Muslim point of view, was the cause of humanity.

Had not all religions declared with varying emphasis and

in different accents, but still declared, that man had been

made after the image of God? So Jesus and Muhammad taught

them, and the latter enjoined them to imbue themselves with

divine attributes. He wished the world could accept this and

make this its one and only religion, for mankind could then

be guaranteed to be in the time to come free from the trouble

that was all around them at the present day.

The opening chapter of the Quran disclosed the four attributes

of Allah. He was Rabb-ul-alameen, the creator, maintainer,

nourisher and evolver of all nations. In His providence He

knew no difference between man and man, no distinction between

race or colour, and no partiality for a creed or a class.

His blessings are open to all and upon all. Let those, then,

who were the rulers of the world follow Him in this and so

secure the peace of the world without the mockery of Genoa

and the hopelessness of the Hague Conference. Today they called

a nation bandits or cut-throats, and tomorrow they shook hands

with them as gentlemen, simply to serve their political ends

and to bring another nation to dust. That was not the way

to restore peace on the earth.

It was immaterial to a Muslim whether the Government of a

nation belonged to A or B. It was like the sunshine, not confined

for good to any place. But if a nation desired to secure the

stability of her rule over other nations, then let that nation

observe the great and divine moral of which he spoke. In that

case the distinction of nationality would disappear, and the

ruler, though of a different colour, would be one with his

people.

They complained about the unrest in India with a sort of

boredom not unmingled with disgust — but India was a

country very rich in Nature’s gifts, a country of almost

limitless resources, and yet it was a country where a very

large number of the children of the soil were living on the

verge of starvation, and where people were existing on a few

shillings a month. He was in England in 1918, when the influenza

epidemic was playing havoc throughout the whole world. It

made its appearance in this country as well, and the then

Government was given notice by the public to combat it. Every

scientific means was resorted to, and the epidemic was stamped

out with comparatively little loss of life. But had they ever

thought of India? India within three months lost three million

souls, equal to the number of all our casualties in the whole

war. A ruler, if he sought to follow the attributes of God,

should of his own beneficence take every measure, hygienic

or sanitary, so that the good health of his people might be

secured and maintained. The whole strife between capital and

labour would come to an end if the employers would, so far

as lay in their power in this respect, imitate their God.

At midday luncheon was provided, the fare consisting of native

dishes in the form of pulao (rice cooked in meat), potato

curry, kofta curry and jelly, and in the evening those who

remained partook of tea. |

Note: There are two more reports of this occasion from newspapers

quoted in The Islamic Review (Evening Standard, August

4th, and Woking Herald, August 11th) which we omit to avoid

repetition.

Woking Mission’s own report of the occasion

A report of this‘Id-ul-Adha written

for the Mission by Rudolf Pickthall appears in The Islamic Review,

October 1922, on pages 404–408. Its text is quoted below.

EID-UL-AZHA 1340 A.H.

A MORNING of low grey clouds and drizzle,

shiny roofs, dripping trees and sodden grass was not an inspiriting

prospect for the Feast of Eid-ul-Azha — Qurban Bairam, celebrated

at the Mosque, Woking, on Friday, August 4th.

Had the rain not ceased, and the clouds lifted, towards eleven

o’clock, thus enabling the Prayers to be recited in the open

air, the tiny Mosque would have been woefully inadequate for the

needs of the occasion, and much of the dignity of the proceedings

must necessarily have been sacrificed.

As it was, the numbers that attended, small though they were in

comparison with former occasions, more favoured by the weather,

taxed the limited accommodation of the Memorial House to the utmost

during such time as the rain continued to fall. Happily the timely

change in the forenoon proved sufficiently lasting to render the

day, in spite of all drawbacks and disappointments, one of real

pleasure and not a little profit.

For the stranger, whether devout Churchman or a seeker after faith,

or even if he be a twentieth century post-war Gallio, stoutly professing

to care for none of these things — well content with a cross

between the perfunctory piety of the daily press and the theological

finalities of Mr. Wells — there are two things in Islamic worship

which can scarcely fail to impress, two characteristics which set

it strangely apart from the idea of worship as conceived and as

practised by its great militant rival.

Concerning the first — simplicity — I have already ventured

to write in these columns; of the second — unity — I would

suggest that it has, if possible, an even greater significance.

The conception of unity commends itself variously to various types

of mind. The Catholic maintains the unity of his faith by the simple

process of shutting out the non-Catholic, and the non-Catholic returns

the compliment with zest.

Each from his own point of view — if he be sincere and not

a mere ecclesiastical casuist — is, no doubt, justified. Sincerity

is apt to be narrow-minded, and to such the formula, “This

is right, therefore that must be wrong,” becomes irresistible,

leading to the wholesale manufacture of heretics and souls self-doomed

to perdition. I repeat, to a sincere man, and to such an one only,

this condition of mind, if not to be commended, is at least logically

justifiable, because it is born of conscience; but that it can ever

in this world make for unity — other than such unity as that

which the Holy Inquisition sought to establish in Spain and elsewhere

— will hardly be suggested. At this present period of history

there is no sign of it, but we have, on the other hand, the three

hundred and forty odd sects and denominations recorded in Whitaker’s

Almanac, with all that they imply.

The Primitive Methodist will shudder at the idea of the Mass,

the Papist wax contemptuous at the mention of the Lord’s Supper.

The Anglican priest denies any spiritual status whatever to the

Baptist minister, and the Quaker will have no truck with either

of them; Lutheran and Calvinist are, in each other’s eyes,

as far apart as Hell and Heaven, and the Plymouth Brother is a law

unto himself.

If it be argued that all this is inevitable after the turmoil of

two thousand years, then it is but fair to turn to Islam with her

thirteen hundred years of warfare, and see how she has fared. There

were assembled at the Woking Mosque on this Friday of Eid-ul-Azha

some two hundred Muslims, comprising representatives of practically

every race in Europe, Asia and Africa; and not only of every race,

but of each and every sect — or more properly speaking —

school of thought in Islam, many of them, no doubt, accustomed themselves

to lead the prayers on Fridays or at Festivals, yet all following

the one Imam — as a matter of course.

It may be said that a similar phenomenon, or one at least in some

respects analogous thereto, is not unknown in Christendom, when

the Churches (that of Rome excepted), on occasions of national or

other importance, hold what are termed special “united services.”

But union is, alas, not always strength, and unanimity, as often

as not, makes but a sorry cloak for compromise.

At such times, all denominations sink their differences for once

in a way, as a special concession, as it were, to what, it is conceived,

may be perhaps after all, the prejudices of the Deity they profess

to worship. Yet even here the conduct of the united service must

be very tactfully apportioned between the spiritual leaders of the

proceedings — a minister of one denomination reading the lesson,

of another offering prayer, of a third delivering an address, of

a fourth giving out a hymn, and so on — lest any one of them,

feeling “out of it” or otherwise aggrieved, should retire

in dudgeon and the harmony be marred.

And it must be borne in mind that such demonstrations of Christian

unity derive their importance solely from the fact that they are

exceptional — which being so, any suggested analogy with the

unity that signalizes Islamic prayer, falls to the ground. For in

Islam this unity is not exceptional — it is a matter of course;

the “two and seventy jarring sects” to which Fitzgerald’s

Omar makes reference — leaving academic dispute to its

appropriate time and place — are as one in the presence of

God; and every Friday in every mosque throughout the Muslim world,

such a united service takes place — as a matter of course.

For of “sects,” in the sense in which that word has

become familiar to Christ’s Church militant here on earth,

Islam knows nothing. The Holy Quran, the rock of its foundation,

whereon it stands away and aloof from the murmur of the tides of

scientific progress or Higher Criticism, permits of no two interpretations

of any one of its essential truths; so that the schools of thought

(or sects, as they have been erroneously termed) into which it must

needs be that any society of human beings, however blessed in its

inception, will in time, inevitably become divided, dispute among

themselves concerning the lesser matters of the law only, because,

with respect to the greater, there is no dispute.

The sermon of the Imam, Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din (and where will you

find two hundred Christians representing all denominations assembled

together on a Sunday or day of festival to hear, let us say, the

Bishop of London — as a matter of course ?) had for its subject

the religion of Abraham and the religion of the Muslim. The learned

preacher, with forceful eloquence and an admirable lucidity, presented

to his hearers the guiding principle of the Faith of the Patriarch,

and of the Faith of Islam in its simplest form, to wit, that it

is the duty of man to strive in all things to obey the behest of

his Maker, and humbly to seek to imitate the example of the Highest

as He has revealed it in His creation; and deplored the fact that

it is because the rulers of this world have failed in this, that

wars and rumours of wars, social upheavals and abortive conferences

have continued and continue.

We, in England, have a kind of convention whereby religion and

politics are considered to be better apart; and indeed, where politics,

as is generally the case, is another name for ambition, and religion,

as not infrequently happens, a worldly profession, like any other,

it is best that they should be kept strictly separate, if only because

of their sinister resemblance.

But where religion stands for man’s duty to God, and politics

stands, as it should, as an essential portion of his duty to his

fellow-man, it is impossible for them to be separated. Religion

divorced from the things of this world loses at once its raison

d’etre, and if this be true of the individual, shall it

not be true of the nation ?

The rain holding off, luncheon was partaken of on the lawn at one

o’clock, and in view of the eleventh-hour change of plan thereby

involved, the indefatigable staff of the Mission merit unstinted

praise for the admirable manner in which it was served.

The congregation in the afternoon was appreciably smaller, for

the reason that, the day being Friday, many were compelled to return

to business and other engagements; but the audience that gathered

to listen to the Imam’s lecture was a singularly attentive

one, and his thoughtful exposition on the Muslim conception of prayer

suggested what must have been, to most of the non-Muslims present,

an entirely novel point of view.

Tea appeared at 4.30, and with its disappearance a memorable day

drew to its close — a day rendered the more enjoyable, perhaps,

by the thought of what might have been had the weather not so opportunely

cleared.

RUDOLF PICKTHALL

|