| Home |

| History Lord Headley Hajj with Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din: Departure from London and stay in Egypt |

| Personalities |

| Work |

| Photographic archive |

| Film newsreel archive |

| •

Contact us • Search the website |

2. Departure from London and stay in Egypt

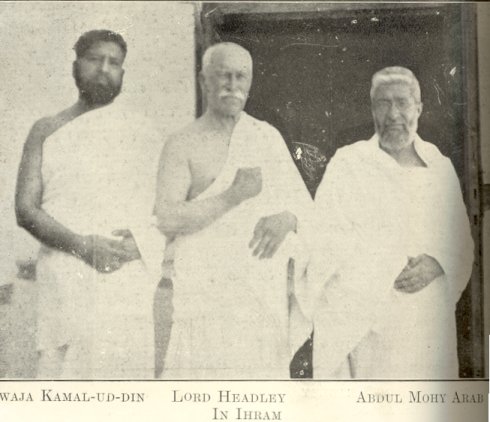

Photograph of Lord Headley (centre)

at the Hajj with two companions. Departure from LondonIn The Islamic Review issue for June–July 1923 (p. 206) it is reported under the heading Where the East meets West:

In The Islamic Review issue for September 1923 there is a report entitled Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din and Lord Headley in Egypt (pages 301–307), which is quoted below. Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din and Lord Headley in EgyptIt was Friday, the 22nd of June. At last Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din and Lord Headley set out on their long-contemplated pilgrimage to Mecca, Abdul Mohye, the Mufti of the Mosque, Woking, accompanying them. It was a long-contemplated pilgrimage. Soon after his declaration of Islam in 1913, Lord Headley’s thoughts were set on a visit to Mecca and Medina. Consequently in 1914, when Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din made up his mind to undertake a pilgrimage His Lordship seized on the opportunity. All preparatory arrangements were made; even passages were booked by the s.s. Persia of the P. & O. But as a bolt from the blue came the Great War and set at naught the entire plan. His Lordship’s children were at the time all minors, and in those troubled days it was not advisable to leave them alone. With great dismay he had to give up the idea so dear to his heart, the Khwaja proceeding by himself. 1918 saw the close of the war, but normal travelling conditions were long in coming. Even so late as the end of 1919 there were practically no facilities. The Khwaja was in the meanwhile in the midst of his kith and kin in India. His return in 1921 roused his [Lord Headley’s] thwarted longing once more, and at last came the fulfilment. Pilgrimage is obligatory on every Muslim of means, and year after year, as a matter of course, the Holy City of Mecca is the resort of hundreds of thousands of pilgrims. But Lord Headley’s pilgrimage has a peculiarity of its own. Lord Headley is the FIRST MUSLIM of this country, and now he is the FIRST PILGRIM from this country too. It was but natural that everywhere the news should have roused special interest. The s.s. Macedonia, which carried the pilgrims, was yet tossing on the Mediterranean waters when a wireless message hastened to bring the warm greetings of Port Said. It was from Ahmad Sanabari Bey, President-elect of the Reception Committee, extending to the illustrious visitors the hospitality of the town. July 3rd, the day on which the pilgrims’ boat touched Port Said, presented a striking spectacle. It was a surprise to all on board to find that about fifty of the gentry were already at the docks to extend them a cordial reception. The boat halted at a distance from the coast. The deputation, however, made their way to it, and assembled in the first saloon. It was then discovered that the representatives of Cairo and Alexandria were also there with invitations from those cities. Mr. Najib Bey Barada, Barrister-at-Law, in an eloquent speech, welcomed the guests to Egyptian shores, in the course of which he made reference to the Quranic verse: “Behold the Sun and his light; and the Moon when she borrows light from him.” Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, he observed, was the spiritual sun that had dawned on the horizon of the West. Lord Headley, having, like the moon, absorbed his light, was shedding his lustre amongst his countrymen. Mr. Najib Bey was followed by Mr. Sanabari Bey and a number of men of learning from Cairo, Port Said and Alexandria, all extending their hearty welcome on behalf of their respective towns. Over twenty gondolas were there to carry them back to the coast. The first boat was occupied by the Khwaja, His Lordship, and Mr. Najib Bey. In the second were Sheikh Abdul Mohye, Al-Mufti and a few of the hosts. The rest followed in a line. In the same order the party got into coaches and, forming a sort of procession, went through the town. In about half an hour the guests arrived at the house of Khalil Kassifi Effendi, situated in the European quarter. Many others of the nobility of the locality came to see them there. Late-afternoon prayers were said in the Khalili Mosque, which goes after the name of its founder, Khalil Effendi. Short speeches were made there. The Khwaja was requested to deliver the sermon, which he did. Lord Headley also briefly addressed the congregation. Then came an evening party in honour of the guests, attended by the cream of the society. Lord Headley, on behalf of himself and the Khwaja, thanked all present in most appropriate words. The next day found the guests on their way to Cairo. The Port Said Reception Committee had arranged for a railway saloon at their own expense, which was occupied by the guests with the hosts from Cairo and Alexandria. From Port Said right up to Cairo, the train passed no station, great or small, but found a large gathering for the guests. Everywhere people would shake hands with Lord Headley and reverentially kiss the Khwaja’s hands. Young and old joined together in lusty cheers of “Long live Lord Headley!” and “Long live Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din!” At such of the stations where stoppage was not less than three or four minutes the guests would speak a few words, which Mr. Najib Bey interpreted into Arabic. About twelve o’clock the train reached Cairo station, which was crowded to the last inch. The high and the humble were alike there to do honour to the guests, who were presented with pretty bouquets of flowers. In the midst of similar scenes as elsewhere — hand-shaking, hand-kissing, and shouts of “Long live Khwaja and Lord Headley!” — the guests were seated in motor-cars and driven to Bekri Mansion, which is situated in Heliopolis. It is the residence of Syed Ihsan Bekri. Ihsan Effendi is well known to most English Muslims. He has been in England for a considerable time, and during his stay took great interest in the Woking Mission activities. Cairo entertained the guests for three days. Prayers were said in the Husain Mosque, where the Sheikhs and Ulemas (learned in theology) welcomed the guests after Friday prayers. In the afternoon, Syed Bekri, the elder uncle of Ihsan Bekri Effendi, entertained them at an evening party. Five hundred people, representative of all stages and grades of society, assembled in the courtyard of a palatial building, presented an impressive scene. The whole arrangement was a display of highly refined taste. Before tea, welcome speeches were made. The President of the Reception Committee, Nakib-ul-Ashraf Sheikh Sawi, in a finely worded speech, welcomed the guests on behalf of the city. He was followed by many others, of whom the speeches of Sheikh Bekri and Usman Pasha are especially noteworthy. Poems in praise of the Khwaja and Lord Headley were read. Then came tea, which done with, Lord Headley gave a brief address, Mr. Najib Bey acting as interpreter. Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din was then requested to address the audience. Though half of the assemblage, unacquainted with English, could not understand what the Khwaja said, yet everyone seemed spellbound. Those that could not follow formed themselves in several groups, each group having one interpreter to deliver the Khwaja’s message. So deep was the impression that on every occasion thenceforth there was general eagerness to hear the Khwaja speak on some Islamic subject. So far as expression of thankfulness was concerned, as well as the spread of the Islamic Movement in England, Lord Headley did the part, and did it exceedingly well. Lectures on Islamic topics fell to the Khwaja to deliver. All the lectures of Lord Headley were reported in the local English papers. After a three days’ memorable sojourn in the midst of Cairo friends, the guests, in company with some notables, left for Alexandria. There the reception was unique. The nobility and the Sheikhs all came to greet and welcome the guests. His Highness Prince Umar Tusan also joined in the general welcome through a representative. Certain features of the reception accorded to the Khwaja and Lord Headley in these Egyptian cities are particularly noteworthy. In the first place, the reception was not from one particular class of people. All classes showed equal zeal in showing their recognition of the Khwaja’s services in the cause of Islam, and their affection for Lord Headley. A spirit of fraternity pervaded the atmosphere. The interest of the higher classes may be judged from the fact that in Alexandria, H.H. Prince Umar Tusan was, in person, the President of the Reception Committee. Prince Tusan is a bright gem of the Egyptian Royalty, and occupies the foremost rank in the Royal Family. On the first day an evening party was held in the guests’ honour, and on the second, a great banquet in the Savoy. Almost all the Sheikhs, the Ulemas, members of the Royal Family, Government Ministers, big merchants and leading men of the town, were present. Secondly, it must also be noted that in this general display of fraternal sentiments the Sheikhs and Ulemas took a foremost part. As a matter of rule, religious heads and teachers, to whichever religion they may belong, keep aloof from such activities. But the Egyptian Sheikhs and Ulemas must be regarded, in this case, as a remarkable exception. They left no stone unturned to do all honour they could to the guests. To honour a guest is characteristically an Islamic virtue; but what is more, of these guests there was one who had endeared himself to the entire Muslim world through his selfless services. These Sheikhs and Ulemas hardly left a word of respect, regard and affection unuttered in respect of the Khwaja. Thirdly, the entire Press of Cairo, Alexandria and Port Said took a real interest in this reception. All papers, without distinction, ungrudgingly opened their columns for reporting the movements and activities of the guests. Gratitude is particularly due to the Christian papers which, notwithstanding references to Christianity in the various speeches, showed no narrow spirit of rivalry. Fourthly, although the movements of the visitors were confined to but three Egyptian cities, the cordial sentiment was shared by almost the whole of the country. As stated, the train passed no station but crowds of country folk flocked to show their love. Letters and telegrams were received from numerous places requesting a visit on the return journey from Mecca. Fifthly, there were many who were anxious to treat the guests to individual hospitality, which the Management of the Reception Committee did not approve of, as being incongruous with the idea of National hospitality. The guests were, so to say, regarded as National guests and welcomed on a National scale. Sixthly, the reception was unprecedented, especially at Alexandria, where Prince Umar Tusan was the moving spirit of the whole thing. The local papers made mention of this fact. Seventhly, it was but natural that the world of Islam should show fraternal love for their new brother in faith, Lord Headley. But the esteem and regard which every section of society, the Sheikhs, the Ulemas and the nobility in particular, displayed for the Khwaja, were simply remarkable. In their talks and speeches they would pay homage to the Khwaja’s erudition in religious lore, his self-abnegation and his deep insight into the inner meanings of the Quranic words. During their stay at Cairo the pilgrims visited the famous Muslim University, Jami-Azhar. In Alexandria, after paying a return visit to H.H. Prince Tusan, they called at the palace of H.M. King Fuad. His Majesty was at the time out of the town. They they paid a visit to Lord Allenby, who received them with all pleasure and courtesy and invited them to dinner, which they were unable to accept for pressure of engagements. The 11th found the honoured pilgrims at Suez, whence they sailed for Jeddha. Gratitude is particularly due to Ihsan Bekri Effendi and Mr. Najib Bey Barada, who spared no effort to afford the guests every comfort. They sacrificed the whole of their time for the latter’s company, which they never gave up till the hour of departure. In fact, Ihsan Effendi’s whole household was every moment at the service of the guests. Note by Website Editor: In a report by Lord Allenby to the British Foreign Secretary, which is on our website, he refers to his meeting with Lord Headley and Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din. |

the successor of the Woking Muslim Mission.